Updated 10 November 2024

A version of this piece appeared originally in the Chicago Reader.

The city of Chicago announced last week that it's about to launch a thorough study of police staffing, resulting in department-wide recommendations to be shared publicly.

Details of the workforce allocation study, which could cost over $750.000, have yet to be widely disclosed by the city or the Chicago Police Department (CPD).

This effort grew out of the federal lawsuit Illinois v. Chicago—a simple name that belies the profound impact it aims to have on CPD.

The chilling antecedent was the 2014 murder of Black teenager Laquan McDonald by white Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke. The shooting was captured on a police dashcam video, initially suppressed by the administration of then Mayor Rahm Emanuel.

A year later, a Cook County judge ordered the release of the jarring video. It spurred a U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation of CPD (and arguably scotched a third term for Emanuel).

In a 2017 report, DOJ wrote that CPD had engaged in a longstanding, pervasive "pattern or practice" of civil rights abuses. Later that year, the Illinois attorney general and a coalition of community organizations filed Illinois v. Chicago in federal court, asking the court to force reform on the department.

The suit resulted in the 2019 consent decree. This 230-page document dictates hundreds of reforms that CPD must implement under the supervision of a federal judge—and with continuous scrutiny by an independent monitoring team, headed by former prosecutor Maggie Hickey, and financed by Chicago taxpayers.

Within the consent decree's 600-plus paragraphs are a half-dozen dictates about how CPD deploys its workforce, including provisos that CPD must:

- Have plenty of mentoring cops ("field training officers") to coach rookies on the job.

- Set and keep a 1:10 ratio of field supervisors (sergeants) to officers.

- Not move supervisors around, so that officers consistently have the same boss. (A rather tricky requisite: At an October consent decree hearing in a federal court, Assistant Attorney General Hannah Jurowicz said, "We have seen that supervisors have [moved] frequently based on seniority," thanks to union contract provisions.)

- "Fully implement and maintain a staffing model" that establishes supervisory limits and stability.

So, how well has CPD done on workforce requirements?

In her October 2021 semiannual report, chief monitor Hickey wrote that CPD's "most notable obstacle for gaining compliance with" the consent decree's workforce mandates "is the absence of a comprehensive staffing study."

Now, fast-forward to Oct. 30, 2024: At a meeting of the city's Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability (CCPSA), Commissioner Abierre Minor announced that "the workforce allocation study is almost ready for launch."

* * *

It's not like they haven't done this before.

At a CCPSA meeting on Nov. 2, 2022, then Chief of Patrol Brian McDermott explained how his bureau reallocates the CPD workforce from day to day.

"Every single day my office does an analysis of where our emerging crime trends are, where we need the most of our deployments," McDermott said. "We focus on our busiest districts."

"Let's just say," McDermott continued, "the 12th District gets hot—or the 4th District, like it got hot this weekend. As soon as we're starting to see an increase in shootings in the 4th District, I'm coordinating with my deputy chief, and we're moving resources from other areas of the city to assist in those areas."

Apparently, such practices continue to the present.

At a June 27 police district council meeting on the North Side, a resident asked District Commander Melinda Linas how tactical—or plainclothes—officers are allocated.

"A lot of our deployment of resources is based on data-driven analysis," Linas replied. "It changes day to day, depending on what's going on in the district, what events are going on.

"If we have . . . robbery sprees," she continued, "we would analyze that data and that of the surrounding districts. And we would kind of analyze where we think those sprees are going to happen . . . and we'd deploy to those [areas] based on the need, or the perceived need, based on the data."

The sparkle of police data, however, fades in the piercing glare of the city's Inspector General, Deborah Witzburg.

According to Witzburg, CPD can't tell how many cops are working where, citywide, on any given day.

While testifying at a Sept. 26 joint meeting of the City Council's committees on Public Safety and Police and Fire, Witzburg called CPD's patrol staffing data "incomplete and low in quality." (Although patrol staff doesn't include positions like detectives and internal affairs, it comprises over three-fourths of department staff, according to the city's 2024 budget ordinance.)

"[T]he police department's data does not lend itself to a good and clear view of how many people are working at any one time; the data is stored in too many different places," Witzburg said. "That's a problem for us from an oversight perspective. It's a problem for the department from a management perspective."

It's also a problem for Chicago residents frustrated with a perceived lack of police response, and for activists who push for greater police accountability.

In 2011, for example, the Central Austin Neighborhood Association (CANA) sued CPD over its poor response to life-threatening emergencies in Black neighborhoods.

CANA, with attorneys of the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois (ACLU), settled its suit with the city in 2021. The city agreed to improve its published records about 911 calls and police response times, and incorporate "equitable police response to calls for service into any new staffing plan."

That's when CPD's inadequate data came to the fore, according to Alexandra Block, ACLU's Director of Criminal Legal Systems and Policing Project.

"To see if the city is complying with the settlement in that case," Block said, ACLU looked into "determining what would be equitable response times. And we [repeatedly] got the same answer from the city: They can't tell us how many people are actually working on any day, on any shift in a given district, because they are not automating and keeping that data—which is just really stunning to me."

Block's view was echoed by Second Ward Ald. Brian Hopkins. "Most of us don't have a definitive number" of officers working in particular wards' police districts, Hopkins said in an interview. "And when we ask, we don't get an answer."

These concerns were corroborated in a July report by the city's Office of Inspector General (OIG). When CPD members are absent from work, the report said, "they are still captured in the data" as physically present. Also, CPD assigns some officers to specialized units that work sporadically in each of the 22 police districts—"thus increasing the difficulty in measuring how their presence contributes to Department coverage in any specific location."

* * *

In past years, CPD has undertaken—and seemingly ignored and/or not widely released—both internal and external workforce studies, some identified in OIG's July staffing report. Examples:

- In 2010, an external study used "a workload approach to come up with the optimal number of officers" and found that CPD had a "disproportionality of patrol deployment."

- In 2014, an external study recommended that CPD revamp the ratio of supervisors to subordinates, and better train supervisors.

- In 2018, an internal study proposed "a staffing model which provides both 'span of control' and 'unity of command'," based on pilots in three police districts.

Why haven't these studies been publicly considered?

As the author of the 2010 study, Alexander Weiss, wrote: reallocating officers is a "zero-sum game . . . there will be winners and losers"—meaning that, in Chicago, any recommendation that reassigns officers from one ward to another will face stiff opposition by the losing wards' aldermen.

That makes such a study, said Hopkins, "the hottest of hot potatoes."

Another sign of how the city buries such reports: In 2020, 49th Ward Ald. Maria Hadden asked CPD for information about one of its external workforce studies. In a memo by then Superintendent David Brown, Hadden was told that the city's law department wouldn't let CPD disclose the study "because of attorney client and/or work product privilege."

This political and legal obstinacy was finally overcome by the requirements of the consent decree—such that, in January of 2023, CCPSA directed the police superintendent to "update the Commission on the progress of [a] comprehensive workforce allocation study" by June 1 of that year, with a further update by year's end.

Documents obtained by Inside Chicago Government showed that, soon after, CPD leaned in.

In October 2023, "CPD began collaborating with philanthropic groups to fund" a workforce allocation study, according to a memo dated June 3, 2024 by Chief of Staff Dana O'Malley.

Later, in an Oct. 15 consent decree court hearing, CPD Managing Deputy Director Allyson Clark-Henson testified that the department "is expected to receive funding" from four organizations: the Joyce Foundation, the Pritzker Pucker Family Foundation, Arnold Ventures, and Chicago CRED. The funding, Clark-Henson said, "is being coordinated through the Commercial Club Foundation, a membership organization for philanthropic sectors."

A source within the funder group, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said, "We believe this study—and some of the related work—is crucial to our larger public safety strategy."

Then, in December of 2023, 47th Ward Ald. Matt Martin introduced—and the City Council later approved—an ordinance obligating CPD to "enter into an agreement with a qualified third party to conduct a comprehensive staffing analysis."

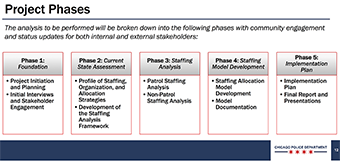

Proposed workforce allocation study phases, as shown in a consent

decree court hearing. Source: Chicago Police Dept.

In her June 3 memo to the mayor and City Council, CPD's O'Malley reported that the department had chosen Matrix Consulting Group of San Mateo, Calif. to conduct the study. On its Web site, Matrix says it's conducted over 350 studies for law enforcement agencies in North America.

According to the court testimony of CPD's Clark-Henson, Matrix will do the study in five phases. The first phase will involve "initial interviews and stakeholder engagements," and in the second phase Matrix will identify CPD's current staffing, organizational structure, and "allocation strategies." The study will include every CPD employee, both sworn (i.e., badged) and civilian.

In the study's third and fourth phases, Matrix will analyze CPD's staffing and develop "an interactive model that can be replicated as needed." Matrix will address the consent decree's requirements noted above, such as a 1:10 supervisor to officer ratio. It'll also figure out where there aren't enough people to do the work, and what sworn positions would better be done by civilians (an analysis also done by OIG in 2013).

What's still unknown is how Matrix will determine CPD’s actual patrol presence in particular locations, which OIG has called "a complex, opaque, and imprecise exercise."

Recently uncovered documentation shows that the funders will pay a maximum of $760,588.

Matrix must deliver final workforce recommendations within 12 months after contracting to do the study.

* * *

Normally, one could find the city's agreements with vendors, and related records such as requests for proposal, via the Department of Procurement Services (DPS) supplier portal. But because the city isn't spending its own money on the CPD workforce study, the whole project is "handled outside of the DPS process," according to a spokesperson.

That's where the transparency challenge starts.

There are many things unclear about the workforce study project, except this: The city has not disclosed key aspects. For example: How was the vendor chosen? How was the $1 million budget (give or take) figured? What's the city's legal agreement with the funders, and how might taxpayers be on the hook? Who, in what city department, is managing the project—especially now that Mayor Brandon Johnson has proposed to cut the CPD office that manages consent decree reforms from 65 positions to 28?

The city has denied or ignored multiple requests for records and interviews that might provide answers.

Ald. Matt Martin (47) talks with Ald. Monique Scott (24)

in the City Council chamber. Photo by Dave Glowacz.

And what's in the vendor contract? The workforce study ordinance requires CPD to sign a contract with its study vendor within 90 days of the law's approval. That date was May 22—a fact that Ald. Martin, the ordinance's sponsor, said had him "incredibly concerned."

"I'm frustrated. And I think, at this point, it's embarrassing," Martin said in an interview.

The ordinance also required CPD to report on the study's progress—to the mayor and the entire City Council—three times between February and September of this year. CPD issued a single update on June 3, which it apparently sent to only one City Council member: Martin.

And, in October, a reporter asked the chair of the council's Police and Fire Committee, Ald. Chris Taliaferro, about status of the workforce allocation study. Taliaferro replied, "What workforce allocation study?"

Finally, in her Oct. 15 court testimony, CPD's Clark-Henson said that each of the project's five phases "will include community engagement and status updates for both internal and external statements."

Observers are ready to engage.

[Editor's note: Despite multiple requests, the Chicago Police Department did not consent to interviews regarding this story.]

* * *

Documents:

■ Complete record of Oct. 15, 2024 court hearing on consent decree (requires Superintendent or higher subscription):

Available only to subscribers. Subscribe here for unlimited access. Subscribers: log in.

■ Transcript of a discussion between Alds. Matt Martin (47) and Jason Ervin (28) about proposed workforce allocation study ordinance at a meeting of the Committee on Police and Fire on Feb. 5, 2024 (requires Superintendent or higher subscription):

Available only to subscribers. Subscribe here for unlimited access. Subscribers: log in.