This week, the Illinois State Board of Elections will certify the state's March primary election results—including those for presidential candidate of the Democratic Party.

What's to certify? Hillary Clinton won Illinois, right?

Well, not exactly.

While Clinton got more Illinois votes than Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, they each will reap a significant number of convention delegates. It's the delegates who will choose the Democratic nominee.

Let's start at the beginning.

The Democratic Party of Illinois will send a total of 181 delegates to the July Democratic national convention. Of these, 102 will have been elected by Illinois voters, with the rest chosen by party bosses.

Around the end of last year, Democrats statewide nominated themselves to be candidates for those 102 slots. These delegate candidates then appeared on ballots in each of the state's 18 congressional districts.

There's no limit on the number of delegate candidates that can run in a congressional district. So if you voted in this year's Democratic primary, you might've seen as many as two dozen delegate candidates on your district's ballot. But the number of delegates that can be elected in a district depends on historical data: It's calculated from the number of people who voted for Democratic candidates in the last several state and federal elections.

On your ballot you also would've seen, after each delegate candidate's name, the name of a Democratic presidential candidate. Here's why: When the delegate candidates filed their nominating papers with the state, most declared their "singular presidential preference"—that is, the presidential candidate they pledged to support at the nominating convention.*

So, how do particular delegate candidates get elected? Here's where things get tricky.

As a result of the March primary, delegate candidates were elected in each district in direct proportion to the number of votes gotten by their pledged presidential candidates—but only for the presidential candidates that got at least 15 percent of the votes in that district.

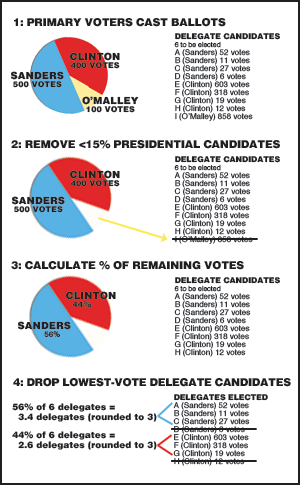

Let's take an example. Say that, in a congressional district, six delegates total can be elected. In this district, Clinton got 40 percent of the vote, Sanders got 50 percent, and former Maryland governor Martin O'Malley got 10 percent. Because O'Malley didn't get at least 15 percent of the district's votes, none his votes would figure in the election of delegate candidates.

To learn how many delegates Clinton and Sanders each would claim, we'd first total the votes that went to just those two candidates. We'd then use that vote total to calculate their vote percentages.

Steps to determine presidential delegates in a sample district

Let's say that the new percentages are: Clinton 45, Sanders 55. This means that, in the district, 45 percent of delegate slots go to Clinton-pledged delegate candidates, and 55 percent of the slots go to Sanders-pledged delegate candidates.

Forty-five percent of six delegates is 2.7, and 55 percent of six delegates is 3.3. Using standard rounding, each candidate gets three delegates.

Given all that, does it matter which delegate candidates got your vote?

It depends. If a presidential candidate earns less than or equal to the number of their pledged delegate candidates appearing on the ballot, all the delegate candidates get elected.

But if, on the ballot, there are more delegate candidates pledged to a particular presidential candidate than the number of delegates the presidential candidate earns, then the delegate candidates who get the most votes win. And if a presidential candidate earns more delegates than ran in a district, party honchos meet in the district later on, and choose from another round of delegate candidates.

Yet another wrinkle: The party requires that an equal number of men and women delegates be elected. The party sets the gender quotas in each district, so that, according to party rules, "the maximum gender variation will be zero."

If you find this confusing, never fear: Your state government has it covered.

The responsibility for all these calculations falls to the office of the general counsel for the Illinois State Board of Elections, headed by attorney Ken Menzel.

Though news media outlets typically report delegate counts with days (or even hours) of a state's primary vote—Illinois is no exception—Menzel said that the state board will certify the final vote counts on April 15.

Before then—given what Menzel called the "Byzantine" nature of the delegate rules—state board staff will check with Democratic Party officials.

"Once we run through [the calculations]," Menzel said, "we do like to bounce it off of them: Do they agree with our interpretation of their rules?"

At this point, though, Menzel said there doesn't appear to be anything unusual about the Democratic delegate election.

The Republican Party delegate winners are a comparative no-brainer. In each district, Menzel said, "the top vote-getters are the delegates—regardless of who they're pledged to."

* Delegate candidates also had the option of being "uncommitted"—pledging to no one. But, according to state officials, no Illinois Democrats opted to do that this year.