Updated 9 April 2019

Chicago's City Council will likely vote soon on whether to lock in payments from property taxes to the developer of the proposed Lincoln Yards complex, plus an undetermined amount of fees to bankers.

On April 10, the council is scheduled to take up ordinance SO2019-2583, related to the Cortland and Chicago River Redevelopment Project Area—also known as the Cortland/Chicago River TIF district. (A previous, 600-page version contains actual ordinance language and hundreds pages of economic disclosures by the various entities having ownership stakes in Lincoln Yards.)

The ordinance is part of a Lincoln Yards funding and rezoning package that Mayor Rahm Emanuel's administration has been hustling through governmental approvals before Emanuel leaves office in May.

Lincoln Yards' 14.5 million square feet of residences, offices, and retail would straddle the Chicago River's North Branch, north and south of Cortland Street.

The complex would sit on what is now largely vacant land formerly used for industrial purposes. So the existing public infrastructure—streets, bridges, water lines, sewers, transit, and lighting—lacks the capacity for all the homes and businesses planned for Lincoln Yards.

The city has proposed a tax-increment financing (TIF) district that would encircle the proposed Lincoln Yards development. The city wants the TIF district, about twice the size of Lincoln Yards, to pay for the public infrastructure that Lincoln Yards would need—and which the Lincoln Yards developer, Sterling Bay, has agreed to build.

The TIF district would pay Sterling Bay for the work by diverting hundreds of millions of dollars in local property taxes away from schools, parks, and county services.

The development has created a chicken-and-egg scenario: All that infrastructure would arguably not be needed if Lincoln Yards wasn't built. So critics say that if Sterling Bay wants to build Lincoln Yards, the developer should fund the infrastructure without a taxpayer payback.

The city disagrees. The area in and around Lincoln Yards would not attract private development without an infrastructure subsidy, said David Reifman, commissioner of the city's Dept. of Planning and Development (DPD).

"The developer needs the public improvements to generate the private improvements," Reifman said in an interview.

In the simplest scenario, Sterling Bay would front the money needed to build each infrastructure project. The improvements would, ideally, cause the assessed values of property in the TIF district to grow. The increased property values would mean higher property taxes, which would then go into the TIF fund. At that point, Sterling Bay could claim reimbursements from the city.

But it's not likely going to be that simple.

Financial structure

The recently released ordinance details the complex way in which the city will provide the reimbursement.

The ordinance embodies what the city calls a redevelopment agreement (RDA).

The RDA details the city's plan to create a series of financial obligations called TIF notes. Each is not quite a loan, but a commitment to pay someone (more on this later) up to $487,830,000 collected from future property taxes.

The $487.8M in notes will pay for 11 separate street, bridge, river wall, and trail projects that would start in 2020 and finish by 2025.

Each note is a legal promise, essentially an IOU. It says that, after the TIF fund accumulates enough property tax revenue, the city will pay the budgeted amount for each of the 11 planned projects. (The least expensive project, improvements to Southport Ave., has a budget of $3.2 million. The most expensive, the realignment of the Elston/Ashland/Armitage intersection, has an $85.3 million budget.)

Each note can be backed by future property taxes from either the entire TIF district or specific properties within the district. So, for example, the city could issue a TIF note that pays for the extension of Dominick St. backed by the incremental taxes from ten surrounding properties. A separate TIF note that pays for the extension of Kingsbury St. might be backed by taxes from five properties close to Kingsbury.

Such notes backed by government revenues are routinely bought and sold in financial markets.

So when, upon completion of a project, the city issues a TIF note to Sterling Bay, the developer can turn around and sell it—thereby getting capital to fund its next infrastructure project.

Or Sterling Bay might hang on to (rather than sell) a note if it plans to own the nearby property for a long time—because it has a stake in the appreciating property values. But if the developer plans to sell off pieces (e.g., a hotel to a hospitality company), it's more likely to sell the note for fast cash, and leave the risk of future payment from increment to the note's buyer.

If Sterling Bay chooses to sell a TIF note, it can sell to either an investor or a lender—depending on who gives them the best deal.

Certain risk-taking investors are attracted to TIF notes. The notes are risky because a noteholder can't be sure when (or even if) the city will pay them off—due to the uncertainty that property taxes will rise in a TIF district.

"The sole source of [the payoff] is the taxes generated by the developer," Reifman said. If the improvements made by the developer don't result in increased property taxes that can pay off the TIF note, he said, investors are "on the hook."

Because TIF notes are high-risk, they offer commensurately high interest rates. Plus, it's uncommon for high-interest-rate instruments to be exempt from federal taxes (as the Chicago notes will be). So it's a specialized investment market.

Sterling Bay can also choose to sell a TIF note to a lender, for better loan terms than it otherwise might get.

For example, say Sterling Bay wanted to borrow $50 million to build the Armitage Ave. bridge. A lender might normally provide a $50 million loan at five percent interest. But If Sterling Bay threw a TIF note into the deal, the lender might provide Sterling Bay a $40 million loan at three percent interest, and pay Sterling Bay $10 million cash for the note.

This is an example, Reifman said, of how a TIF note is "a conduit to a lower cost of borrowing," which results in fewer public dollars spent "because the debt service is less—a lower cost to get the same results."

Another wrinkle: What if the properties in and around Lincoln Yards don't appreciate in value as much as expected? In that case, it'd become difficult for Sterling Bay to use a TIF note to raise capital for an infrastructure project—because investors would see that it's even less likely that property taxes would grow quickly enough to pay off the note. So the city has a plan B: a special service area (SSA) tax.

Usually, an SSA comes about because residents and businesses in a small area want services beyond those that the city normally provides—such as daily street/sidewalk cleaning, security guards, and local business marketing. So, to pay for those things, the locals agree to tax themselves.

If the city sees that properties in the TIF district aren't growing in value enough that the city should saddle itself with TIF notes, it can choose to slap an additional property tax on the properties—in the form of an SSA.

Normally, an SSA comes about because local property owners want it. In Lincoln Yards, because Sterling Bay owns all the properties, the city and Sterling Bay can simply decide to impose an SSA—thereby guaranteeing a property tax source of income for a bond, called an SSA bond, that the city can offer instead of a TIF note.

"What that does," said Reifman, "is it effectively puts a tax lien on the property."

Enacting an SSA, though, would require separate approval by the City Council.

Who are taxpayers paying, and how much?

The redevelopment agreement seems to put a dollar amount on how much taxpayers will end up reimbursing Sterling Bay for its infrastructure work—but the RDA doesn't tell the whole story.

First, the RDA identifies the "maximum aggregate principal amount" that incremental property taxes will pay for the 11 projects identified: $487,830,000.

But a separate document approved by the City Council, the Cortland/Chicago River Redevelopment Area plan (or "redevelopment plan"), shows that the city has budgeted at least $900 million for construction and related expenses (such as land acquisition) in the entire TIF district over its 23-year lifespan.

The redevelopment plan identifies another cost that incremental property taxes will fund: fees that financial and legal professionals charge the city to set up and maintain the elaborate financing scheme. According to the plan, up to $400 million in property taxes will pay for "additional financing costs incurred by the City, including without limitation interest expense, capitalized interest and costs associated with optional redemptions."

Documents for similar city financing show an exhaustive list of services for which the city typically pays: arbitrage, auditors, bond counsel, credit enhancement, disclosure counsel, escrow agents, feasibility consultants, financial advisors, rating agencies, registrars, remarketing agents, securities depositories, printers, third-party trustees, verification agents, and underwriting.

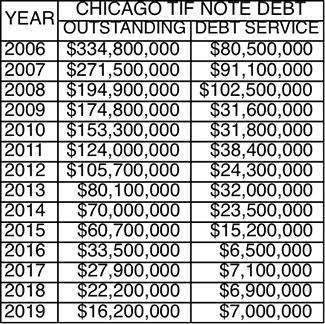

Outstanding TIF note debt as of the end of 2016. Subsequent years

are projections. Source: city of Chicago.

So while the RDA identifies $487,830,000 that'll pay for construction for 11 projects, it doesn't show how much taxpayer money will go toward TIF note interest, plus fees to bankers and lawyers. When grilled about this by Ald. Michele Smith (43rd) at a City Council finance committee meeting, Reifman said "it could be as little as $200 million."

The RDA says that the city must redeem each TIF note within 20 years of issuance or by the termination date of the TIF district. Given that the city's issued TIF notes in the past, it has paid principal and interest ("debt service") on TIF notes for many years. City data show that annual TIF note debt has steadily decreased—though Cortand/Chicago River TIF notes could reverse this trend.

Furthermore, if the city ends up using special service area bonds to finance any project, it will likely pay fees to what the RDA calls a "Third-party SSA Tax Administrator." According to a DPD spokesperson, these fees would be charged against a separate, $25 million budget described in the redevelopment plan as "Analysis, Administration, Studies, Surveys, Legal, Marketing, etc."

Also, the city and Sterling Bay have repeatedly touted the estimated $64 million that Sterling Bay will pay into a city coffer called the North Branch Corridor Bonus Fund. This "bonus fee" is directly proportional to the level of density that Sterling Bay creates in its buildings; more density means a higher fee.

However, the rezoning ordinance approved by the City Council for Lincoln Yards North essentially refunds the fee to Sterling Bay, up to the amount of its costs for extending the 606/Bloomingdale Trail eastward.

Finally, the city's TIF data portal shows that the current North Branch (North) TIF district has a proposed $10 million set aside for new bridges at Webster St. and Cortland Ave.—both of which currently reside in that TIF district. But if and when the Cortland/Chicago River TIF district goes into effect, both bridges will reside within the latter district. In that case, DPD's Reifman said, funds will be transferred (or "ported") from the North Branch (North) TIF district.

The City Council's finance committee is scheduled to consider the proposed Cortland/Chicago River TIF district at a 9 a.m. hearing on Wednesday, April 10, at City Hall. If approved, the district will likely face a full council vote immediately afterward.

After Mayor-elect Lori Lightfoot said that she wanted the council to delay its votes, Mayor Rahm Emanual issued a statement saying that he'd go along—after which the council's finance committee delayed its vote by two days.